|

ARCHIVE # 4: 554 ARTICLES (NOV -SEPT 2006) |

|

|||||

| Visitors Since 03/2006 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Click here to read messages from our MySpace Friends HERE'S A FEW OF OUR 1,404 MySpace FRIENDS |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Click to view 1280 MS Walk photos! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "Join a trial at Barrow & receive all medication & study based procedures at no charge!" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stan Swartz, CEO, The MD Health Channel "WE PRODUCED THE FOLLOWING 9 VIDEOS FOR YOU!" Simply click the "video" buttons below: . |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Previious Posts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MS NEWS ARCHIVES: by week | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| September 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| October 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| November 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| July 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| April 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sunday, November 26, 2006

University of Rochester presses quest for stem cell breakthrough - Democrat & Chronicle Newspaper

Pursuit of new disease treatments is building momentum with the work of key researchers

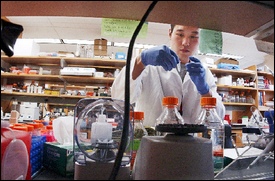

(November 26, 2006) — Quietly but steadily, under the watchful eye of some of the nation's top scientists, hundreds of technicians and researchers isolate cells and scrutinize data in 18 immense laboratories at the University of Rochester Medical Center. They're teasing out the secrets of stem cells, the building blocks of the body, in the hope of finding cures for diseases such as Parkinson's, diabetes and multiple sclerosis.

Some of the work has sparked controversy because it uses days-old human embryos, which some researchers believe can develop into many tissues of the body and in larger quantities than possible with stem cells taken from adult tissue. In turn, discoveries using those cells may lead to many more treatments, for conditions as wide-ranging as spinal cord injuries and blood cancers.

But the issue is not as simple as many political pundits, and some scientists, have led the public to believe. Using stem-cell science to treat people may be close to realization for some conditions but many years away for others. Federal funding for new embryonic work is banned, but private funding is flowing. Using embryos could be vital for some discoveries but completely unnecessary for others.

One UR scientist, neurologist Dr. Steven A. Goldman, recently had a breakthrough, then a setback, in Parkinson's treatment. Yet he might be close to finding a treatment for some neurodegenerative diseases.

Details of the daily work of researchers such as Goldman are largely unknown to the public, if only because the science is so complex and arcane. But shining a spotlight on his lab may improve understanding of the research that could one day change medicine.

"To think, you can actually start to do the things you dream about," Goldman said.

UR expands reach

Directly across from Goldman's desk in the Arthur Kornberg research building next to Strong Memorial Hospital is a dry eraser board filled with scribbling. The notations would probably mean nothing to 99 percent of the population. But for Goldman, it's like reading the back of a cereal box. "It's pretty easy actually," he said.

Goldman is sketching out what is called a progenitor cell, a cell that leads to the formation of the brain's structures. But one has to determine how and why the cell changes to learn how to manipulate it for other purposes. That's where the mapping of the cell comes in, finding the different genes present in each cell that, with the help of molecular signals, cause the cell to turn into its final form.

The cell sketched in black marker on Goldman's board is an astrocyte progenitor, a cell that eventually turns into the star-shaped network of branches and fibers that make up the physical structure of the brain.